WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Conservative U.S. Supreme Court justices on Tuesday signaled skepticism over the legality of President Joe Biden’s plan to cancel $430 billion in student debt for about 40 million borrowers, with the fate of his policy that fulfilled a campaign promise hanging in the balance.

The nine justices heard arguments in appeals by Biden’s administration of two lower court rulings blocking the policy that he unveiled last August in legal challenges by six conservative-leaning states and two individual student loan borrowers opposed to the plan’s eligibility requirements.

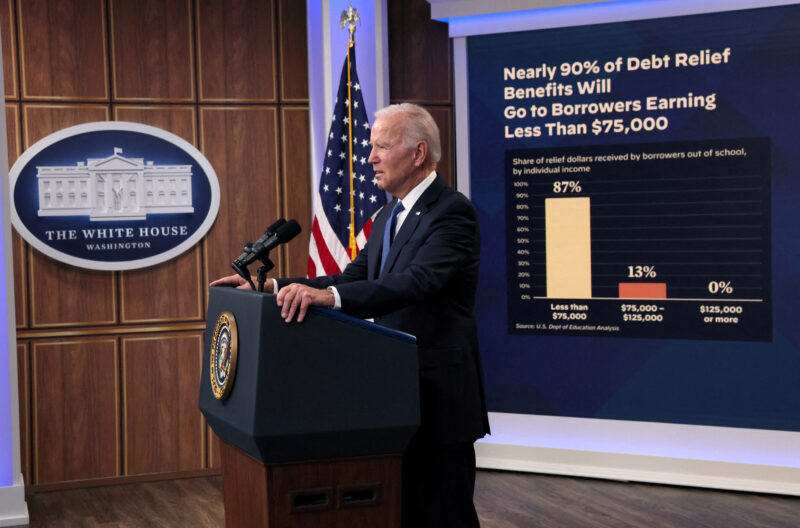

Under the plan, the U.S. government would forgive up to $10,000 in federal student debt for Americans making under $125,000 who obtained loans to pay for college and other post-secondary education and $20,000 for recipients of Pell grants to students from lower-income families.

U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, arguing for Biden’s administration, sparred with conservative justices including John Roberts, Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh over the policy’s legal underpinning and fairness. The court has a 6-3 conservative majority.

Roberts, the chief justice, questioned whether the scale of the relief was a mere modification of an existing student loan program, as allowed under the law the administration cited as authorizing it.

“We’re talking about half a trillion dollars and 43 million Americans. How does that fit under the normal understanding of ‘modify’?” Roberts asked.

The policy, intended to ease financial burdens on debt-saddled borrowers, faced scrutiny by the court under the so-called major questions doctrine, a muscular judicial approach used by the conservative justices to invalidate major Biden policies deemed lacking clear congressional authorization.

Alito challenged Prelogar’s assertion that Biden’s plan does not fit under the major questions paradigm, wondering whether members of Congress would regard, even colloquially, “what the government proposes to do with student loans as a major question or something other than a major question.”

“Of course, we acknowledge that this is an economically significant action,” Prelogar said. “But I think that can’t possibly be the sole measure for triggering application of the major questions doctrine.”

A 2003 federal law called the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act, or HEROES Act, authorizes the U.S. education secretary to “waive or modify” student financial assistance during war or national emergencies.”

Many borrowers experienced financial strain during the COVID-19 pandemic, a declared public health emergency. Beginning in 2020, the administrations of President Donald Trump, a Republican, and Biden, a Democrat, paused student loan payments and halted interest from accruing, relying upon the HEROES Act.

Roberts asked Prelogar whether the case presents “important issues about the role of Congress and about the role that we (the court) should exercise in scrutinizing that – significant enough that the major questions doctrine ought to be considered implicated?”

Biden’s plan fulfilled his 2020 campaign promise to cancel a portion of $1.6 trillion in federal student loan debt. Prelogar sought to cast it as “the administration of a benefits program” rather than an assertion of regulatory power not authorized by Congress.

Republicans have called the plan an overreach of Biden’s authority. Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska and South Carolina challenged it, as did individual borrowers named Myra Brown and Alexander Taylor.

‘MASSIVE NEW PROGRAM’

Roberts told Prelogar the case reminded him of Trump’s effort – blocked by the Supreme Court – to end a program that protects from deportation hundreds of thousands of immigrants, often called “Dreamers,” who entered the United States illegally as children.

Kavanaugh said Congress in the HEROES Act did not specifically authorize loan cancellation or forgiveness and that Biden’s administration pursued a “massive new program.”

“That seems problematic,” Kavanaugh said.

Hundreds of demonstrators including borrowers rallied behind Biden’s relief plan outside the court. Biden wrote on Twitter, “The relief is critical to over 40 million Americans as they recover from the economic crisis caused by the pandemic. We’re confident it’s legal.”

Some Republicans have attacked Biden’s plan as unfair because it benefits certain Americans – colleged-educated borrowers – and not other people.

Roberts presented Prelogar with a hypothetical scenario involving one person who borrowed to pay for college and another who borrowed to start a lawn-service business.

“We know statistically that the person with the college degree is going to do significantly financially better over the course of life than the person without. And then along comes the government and tells that person, ‘You don’t have to pay your loan,'” Roberts said. “Nobody’s telling the person who is trying to set up the lawn-service business that he doesn’t have to pay his loan.”

Prelogar responded to such “fairness” concerns raised by conservative justices by saying that “you can make that critique of every prior” government relief to various Americans under the HEROES Act.

The liberal justices raised doubts that the states had the proper legal standing to sue based on their claim that Biden’s plan would harm a single Missouri-based student loan servicing company, noting that the business did not itself bring the challenge.

The court’s rulings on the matter are due by the end of June.

(Reporting by John Kruzel and Andrew Chung in Washington; Editing by Will Dunham)